The following is an excerpt from The Story of American Furniture (1937) by Thomas Ormsbee

Desks & Secretaries

From the settlement of Jamestown to the close of the first quarter of the 19th Century was a golden age of letter writing and diary keeping. Captain John Smith chronicled the colonizing efforts made in Virginia/ Governor William Bradford did the same for the Plymouth Plantation; Judge Sewall's journal records a wealth of everyday happenings/ the Reverend Cotton Mather likewise omitted from his diary little that was going on about him. Benjamin Franklin carried on a voluminous correspondence at home and abroad and wrote his Autobiography for the benefit of his illegitimate son, the royalist governor of the Jerseys. Washington conducted a large if terse correspondence and left behind him a detailed journal of his conduct of the Mount Vernon estates. John and Abigail Adams by letter bridged the miles which separated them when patriotic duty detained him from home months and even years at a time. Jefferson, too, was always writing letters to express his point of view on important matters. It was a labor of love with no short cuts. The machine on which an individual might type his thoughts was far in the future , and the words "Take a letter, please" were yet unspoken. It was each man for himself with quill pen and in longhand. There was also no postal service. Nevertheless, up and down the coast and back and forth across the Atlantic, there flowed a ceaseless and ever increasing flood of letters anent business, politics, scholarly and theological interests, and family affairs. They were long and usually terminated with "Your humble and obedient servant." Goose quills by the thousands and ream after ream of handmade paper were consumed.

Obviously pieces of furniture on which to do all this writing must have existed from the start. But the early forms were not desks at all. They were, as shown in an earlier chapter, the larger chests in miniature (Illustration 17). Books, writing materials, and particularly treasured possessions were stored within. The flat top was the writing surface. Whether placed on a table, joined stool, or held in the lap, it was anything but a convenient arrangement. Then about 1650 some one thought of a box with a slanting lid and took the first real step toward developing a piece of furniture especially designed for writing, the desk. The first of these, save for the lid that sloped upward and away from the person using it and was hinged at the high side, was no different from the flat-lidded boxes. Then came compartments for paper, quill pens, inkpots, and sand boxes, the substitute for blotting paper until well in to the 19th Century. Twenty inches from front to rear, sixteen wide, eight high at the back, and four at the front were the dimensions of a box of the slant top variety. It was provided with a lock and key, and the side were generally ornamented with shallow carving more or less geometric in design. Still it was a writing box to be placed on a table when in use, and so its size was kept small enough for easy handling. Then it was made somewhat deeper and into the added space a drawer was introduced. The woods used for these early forms were oak for better-made ones and pine for the cruder.

The next step in the evolution was to make the box larger and rest it on a supporting frame of turned uprights and square cross-members, structurally the same as those of the early tavern table. And now we see it emerging from the polliwog stage and becoming a true desk. As our cabinetmakers continued to make these boxes on frames, they increased their size and sometimes added a drawer (Illustration 53). The chest, too, was developed into the chest of drawers and had its effect on desk design in two ways. A rectangular enclosed frame fitted with several drawers was substitute for the supporting frame; the slanting lid was hinged at the bottom, and the angle of its slope increased. No more groping around in the compartments beneath for needed supplies with one hand while the clumsy lid slipped out of the other and descended with trying results on wrist and temper. The lid now folded outward and rested firmly on sliding bracket supports beneath. Thus, when the desk was open the things kept in the pigeonholes were directly before the writer and readily at hand (Illustration 54).

When the writing box was thus wedded to a frame and became a desk, making of these primitive forms more or less ceased until the Empire and Sheraton years. Then many small, oblong writing boxes with top and bottom separated by a slanting cut were produced. They were chiefly made of mahogany mounted with brass escutcheons, corners, and edges. They had ingenious compartments for writing supplies, correspondence, and sometimes hidden recesses for confidential memoranda and money. Lawyers who rode circuit in the first quarter of the 19th Century were partial to these latter-day variations of the Puritan Bible box. One inherited by the author from a legal great-uncle had all its interior lined with red morocco. When the lid was laid back, it exposed a slanting writing surface ten by sixteen inches with pen tray , inkpot, and sand bottle at the top. The upper half of this was hinged, and beneath was a place for writing paper and the like. Beneath the lower half of the writing surface, also hinged, was a tray of toilet articles such as razor, lance for blood letting, a glass jar holding an ounce or so of snuff and a most efficient corkscrew. Originally there was a cowhide leather case into which the box could be slipped for protection when taken on stagecoach journeys - the 1825 version of the combined brief and toilet case. Can you see a 20th Century sales manager or corporation attorney with such a writing box before him as he endeavors to continue work while aboard a limited transcontinental train or airship?

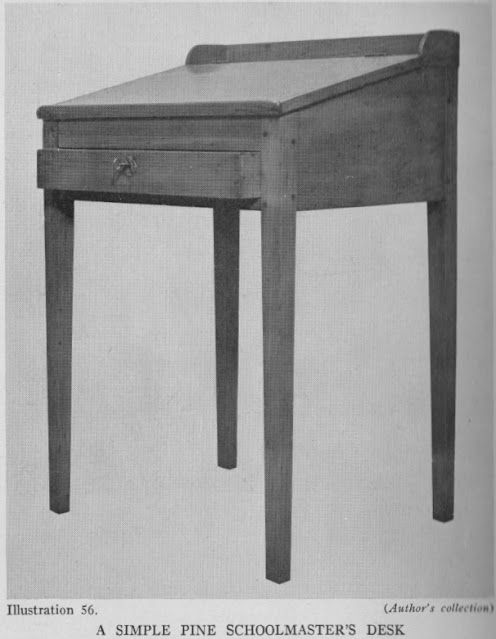

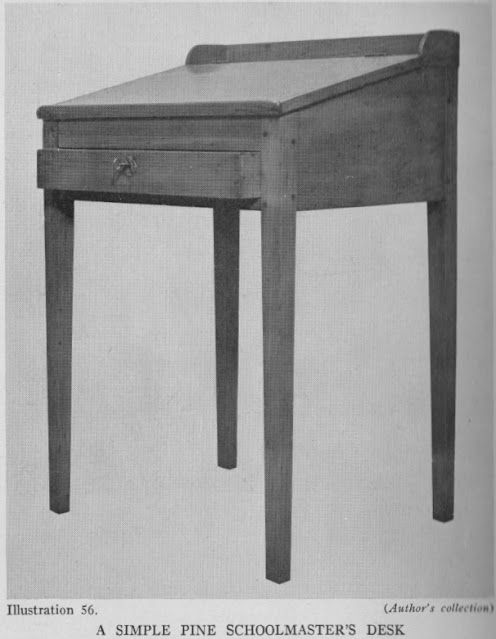

As the slant-top desk came about when the William and Mary style was in vogue, American craftsmen naturally made this pieces with the ball or turnip foot and other ornamental designs of the period (Illustration 55). They also continued to make their smaller desks with the framework base of the tavern table. The more elaborate had the lid hinged at the bottom, while the simpler types reverted to the earlier form and were hinged at the top. Some had a drawer inserted in the upper section; others were made wit a second one located in the top of the supporting frame. Craftsmen showed that they realized they were combining the old writing box with a frame base, for they made them separate. In an emergency the piece could become dual-purpose by removing the upper box and substituting a table top. This primitive desk design persisted longer than is commonly realized. With lid hinged either at top or at bottom, but more frequently the former, it was the model for a long line of schoolmaster's and countinghouse desks all through the 18th and the first half of th 19th Century. The various style periods affected it slightly both ornamentally and structurally, and toward teh last it was made in a single piece rather than in two part (Illustration 56).

During the Queen Anne years, desks were principally made with a frame base similar to that used with chests of drawers. Here either short turned legs ending in button feet or longer cabriole legs with the Dutch foot were in place of the trestle taken over from the tavern table. Sometimes the horizontal pieces connecting these legs at the upper ends - there never were any cross-members near the floor with Queen Anne desks or chests of drawers - were cut in valance lines to provide that characteristic ornamental apron. Within the upper part the simple partitioning which formed the pigeonholes of earlier days was replaced by more elaborate work, and a number small drawers added (Illustration 57). This was to reach its high point during the Chippendale years to follow. Then came a multiplicity of compartments and often secret ones skillfully concealed. As a usual thing these hiding places are locating behind the central section or on either side of it. With the latter, a pilaster of the split banister forms ornaments the front of a tall, deep, but thin drawer called a document box. A pin or peg that is released by finger pressure is the usual manner of holding the concealed containers that flank the central section (Illustration 58). To locate the releases, feel carefully for the button or pin. With the former a slight pressure will release the compartment as it generally has a wooden spring at the back which forces the whole container out a little when the retaining button is depressed. With the pin type, simply pull out the pin. When the secret space is behind the centre section, there are usually two small, thin wooden bolts, one on either side, that hold it firm and can be released by sliding inward. Usually such catches have a little depression in their outer surface into which the tip of the forefinger fits naturally.

These secret compartments are a fittng rival to the buried treasure of Captain Kidd for the false hopes they raise in the human breast. Repair men refinishing desks so tricked out the always hope to run across pine-tree shillings, valuable letters or signatures, Continental paper currency, or original documents. Always the are disappointed. It is apparent that the original owners of such desks did not highly regard their secret spots as places of safety and seclusion. Nevertheless, there is an interesting air of mystery about them, and in their making the old cabinetmakers frequently did very fine work, which of itself materially increases the value of a piece.

Under the influence of the Chippendale style American craftsmen adhered closely to the design and structural plan they utilized in making chests of drawers. Most of the desks had four drawers, a slanting front that rested on sliding arms or brackets, and either short cabriole legs terminating in claw-and-ball feet or bracket feet which might or might not be developed with molding elements on the outer surfaces. Two features marked these desks. The first was the wealth of ornamental detail and fine workmanship lavished on the pigeonhole compartments in contrast to the simple interiors of the two preceding style periods. The second feature was the addition of an upper or bookcase section. This caused the piece to take on such imposing proportions that the simple Anglo-Saxon term "desk" seemed quite inadequate. So from the French escritoire was derived the well rounded, sonorous word "secretary." A distinction without difference, and a choice morsel for philologists. In short, take off its dignified headpiece, and it is a desk: put it on, and it is a secretary.

The upper sections made at this time were provided with paneled doors and either a bonnet top similar to that of the highboys or a fine cornice in which nice molding and finely executed dentelations were used (Drawing 15). The John Goddard secretaries which he made about 1760 for the brothers Brown, outstanding merchant princes of Providence, are ultimate specimens. They are practically identical. The base is block-fronted with shell carving like the typical Goddard-Townsend chests of drawers. This design is carried out on the outer surface of the slanting lid and in the upper section, where the front is made of three panels, the outer ones being in relief and the centre once again incised. In the interior the effect of the block-fronts and shell-carved lunettes is continued by a centre compartment and others at the extreme right and left in which the drawer-fronts are shaped to balance in reverse the recessed door of the central compartment. Between these on either side there are groups of three pigeon-holes, each with a shallow shell carving at the top. The broken curves with an arched cornice molding. At the centre and outer curves there are three carved finials of the conventionalized flame type (Illustration 59).

Other fine secretaries were made by cabinetmakers in New England and Philadelphia. Some had block fronts; others, the various forms of the serpentine, and occasionally one was straight. Either the flat or the bonnet top was used, but a pair of paneled doors was the rule rather than Goddard's triple arrangement. The interior of the upper part was always divided into a number of compartments of varying sizes for account books, important papers, and the like, thus forming the filing cabinet of th day. On the sides of the lower section and occasionally the upper as well, large brass drop handles were mounted, showing their makers had not forgotten the origin of such pieces and subconsciously added these trappings of the earlier great chest (Illustration 58).

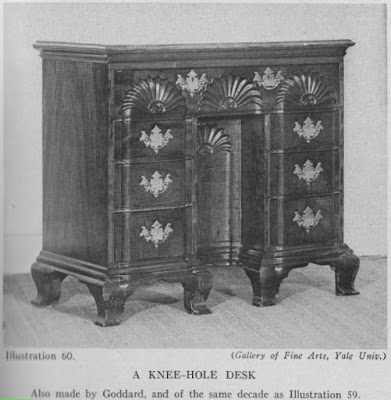

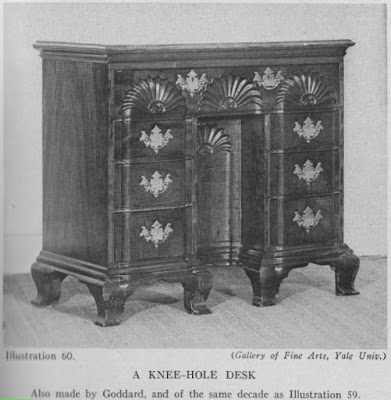

The knee-hole desk, that type with a flat top and, as its name suggests, a recessed centre in the base flanked on either side by tiers of drawers the full depth of the piece, was first made in England during the William and Mary period. It did not make its American debut until the Chippendale era, and even then was seldom produced. Hence American desks of this type are extremely rare (Illustration 60). The Townsend-Goddard group made a few in which they exercise their fondness for the block front. This design fitted the knee-hole type well, and the recessed entre cupboard accentuated it. A few others were made by Philadelphia craftsmen in either mahogany or walnut, but nearly all desk of this sort offered for sale today are of English origin. Those of American make, because of their rarity, are museum pieces and command corresponding prices.

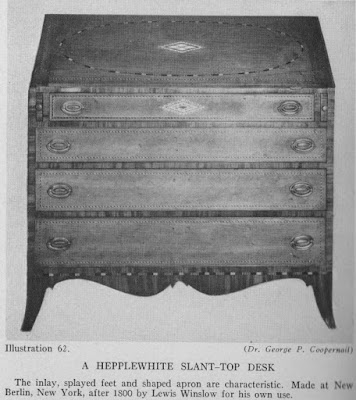

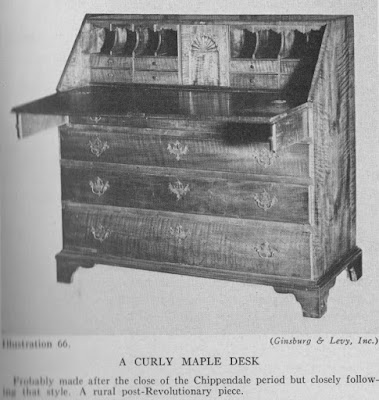

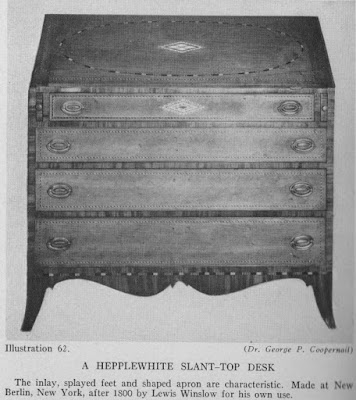

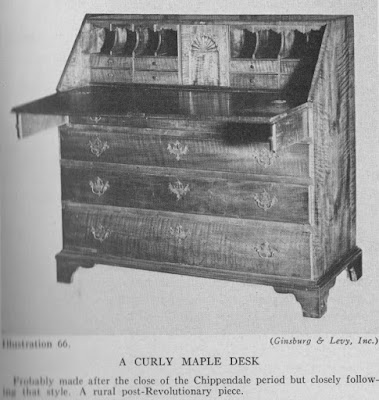

The most popular and satisfactory desk form of all was undoubtedly the regular slant-top with four drawers below already referred to. They were made with block, serpentine, or straight front, had either bracket or claw-and-ball feet and were produced in mahogany, walnut, cherry, plain and fancy grained maple, and even pine. Cabinetmakers of all sections kept to this design of ten or twenty years after the close of the Chippendale period. Some have imposing interiors in which centre cupboard, document boxes, and flaking pigeonholes and drawers are ornamented with shell lunettes, scalloped edges, and half-round pilasters. At the top of each pigeonhole division a small, valance-shaped crosspiece serving as the front of a shallow, inconspicuous drawer was frequently used. As the Hepplewhite influence made itself felt, curly maple became a favorite wood, and in inlay design ornamented the slant top. So practical was the desk form that it did not give way entirely when the Hepplewhite and Sheraton styles gained the centre of the stage. Modified in ornamentation and minor details, it persisted even through the succeeding Empire years. Interiors, however, became simpler and seldom contained any secret compartments.

The Hepplewhite period brought with it a new design of secretary, that with the tambour front - which, being interpreted is finely reeded woodwork mounted on a heavy linen. This flexible arrangement slides back and forth in grooves that may be bent a an angle even as sharp as ninety degrees. A very beautiful detail in the days of its creator, a most atrocious one in the roll-top of a century later. But where the latter-day abominations had flexible woodwork with the lines of ribbing horizontal, those of American Hepplewhite were always vertical. These tambour secretaries were classically simple of line. Tapered legs with their outline continued up to the writing level; one, two, or three drawers of full width, but never descending as near to the floor as with the Chippendale style; a narrow writing-leaf that rested flat when close; a low upper section with a central closet and a pair of tambour slides serving as doors were the structural features (Illustration 61). The one bearing the label of John Seymore & Son referred to earlier is a remarkable piece because of the fineness of its execution. It was mahogany and had a wealth of inlaid ornamentation, of which the finest was the husk festoons that decorated the two parts of the sliding front in the upper section. In this particular piece there was no central cabinet with the door dividing the shutters, which was unusual.

Hepplewhite secretaries were also made with an upper section that had doors. Both types were less formidable and more intimate than those of the Chippendale days. They were never much over six feet in height and correspondingly proportioned otherwise. When there were doors, they were usually made with glass panels set in wooden bar moldings. A typical door of this period would have three panels, each terminating in a Gothic arch. More unusual and probably of country make is the same secretary with solid doors. Here fine crotch-grain mahogany veneer was usual, and the centre of each door had an ornamental medallion of an urn or other classic design. The top was usually finished with a cornice made of flat members that from teh outer finial blocks curved upward to a central pediment block on which frequently rested a gilded eagle with wings outspread - a patriotic touch that combined will with the classic simplicity the brothers Adam introduced to Englishmen and their American cousins.

When working in the Hepplewhite manner on the slat-top desk of the Chippendale ra, our cabinet makers replaced the bracket or claw-and-ball feet with those having the outward splay used with the chests of drawers, and incorporated a similar curved skirt connecting the feet (Illustration 62). Pencil-line, herring bone, and more elaborate forms of inlay outlined the drawer fronts and the upper side of the lid. In addition, inlaid medallions were sometimes placed in the centre of the flap and that of upper drawers.

Another variety of desk was the drop-front. Here is the writing compartment was drawerlike and pulled out for sue. The front was hinged on the lower edge and supported with two curved brass brackets. This type was first employed in England during the Chippendale period, but with rare exceptions was no used by American craftsmen until they were making pieces of Hepplewhite design (Illustration 63A). The fall-front is a most ingenious plan for providing writing space in pieces not necessarily designed as desks. A drawer front is hinged at the bottom and , when the section is pulled out about half its depth, folds down and provides an excellent area for penmanship. The back third of the section is given over to drawer and compartments along the lines of other desks. Sometimes this drawerlike writing compartment was built into a sideboard of the period, replacing the upper drawer of the centre (Illustration 63B). It was then known as a butler's desk on the theory that here household accounts were kept by the major-domo of a family opulent enough to afford such a dignitary. Again it might be a fine chest-on-chest with the upper drawer of the lower section replaced by such an arrangement. The old dual-purpose instinct of the 17th Centre rising again.

American craftsmen again lagged behind their English brethren in the matter of break-front secretaries While there were plenty in the Chippendale and Hepplewhite styles in the old country, the Sheraton influence was in full force before many were made here. On account of their size and cost they were never widely made in America. In fact, it is probable they were only produced on special order of dimension proper for a particular location. Occasionally they are found with some Hepplewhite detail, but even then the Sheraton influence so predominates that it is safe to place them in the latter period (Illustration 64). In construction the break-front is really a fall-front with upper section flanked on either side by added bookcase, drawer, and closet compartments that are a little shallower so that the secretary section projects from four to six inches and dominate the piece. This difference in depth of centre and side parts is of course the feature that gives the name. Such secretaries were usually about eight feet tall and from six to eight wide. The doors of the upper part have panes of glass cut in diamond and other geometric shapes. Being always important pieces, they were made of mahogany, and fine crotch veneer ornamented the drawer and lower doorfronts. There was a curved cornice at the top with four finials and sometimes the gilded eagle mounted on the central pediment block. For ease in moving, these huge pieces were always made in sections.

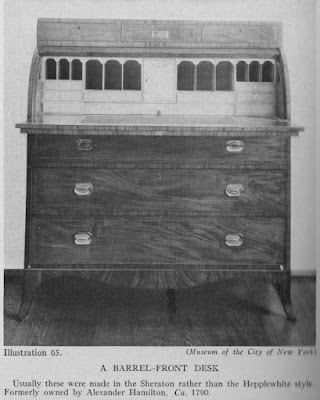

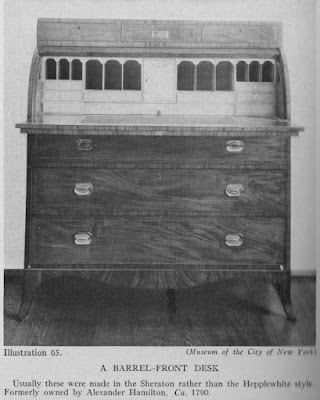

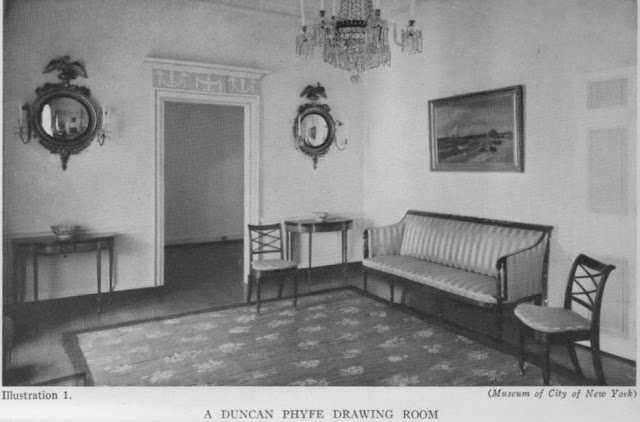

Just as the Hepplewhite influence produced the tambour front, so under Sheraton came the barrel- or cylinder-front. The two ideas were combined in the last days of the 19th Century, and the clumsy roll-top desk already alluded to was the result. Its chief merit was its short life. In the Sheraton barrel-front the sloping lid of former periods was replaced by a quarter-round cover that rotated on its axis into the back of the case when the secretary was opened for use. This curved area was finished with well-marked mahogany veneer, and usually the piece had reeded legs of about fifteen inches. The upper part had doors with glass panels generally cut with Gothic arched tops (Illustration 65). Phyfe and some of the other urban cabinetmakers made secretaries of this design, but craftsmen in country communities seem to have adhered to those which were fundamentally Chippendale in construction (Illustration 66). Sometimes they added Sheraton touches such as the reeded leg and the shallow pilaster. Where, in the chests of drawers, legs that were all but detached from the case were popular as was the bow front, these features were not carried over into desk and secretary making. In some of the secretaries the upper section had paneled doors and a simple broken pediment top, while the lower on e had a fall-front writing section and a large closet with double doors beneath. The whole was supported by simple and fairly low bracket feet.

With the end of the Sheraton period, the well-designed desk may be said to cease. The hapless piece perhaps suffered more than any other at the hands of the American Empire enthusiasts. Secretaries now became a mere ceiling scrapers, eight or nine feet tall with towering bookcase sections that threw the lower half entirely out of proportion. They were made of mahogany and sometimes rosewood; but beautiful wood is not enough, so it is better to pass such pieces by and wait for an earlier example.

For places of public meeting yet another type of desk, the flat-top of impressive dimensions, was made by American craftsmen from the Chippendale years through those of Sheraton, generally with eight legs and an open section in the centre of the base. Present-day furniture makers seem to have followed this style in producing what they unctuously call the executive desk. Consciously or not, they are indirectly copying the most historic American desks.

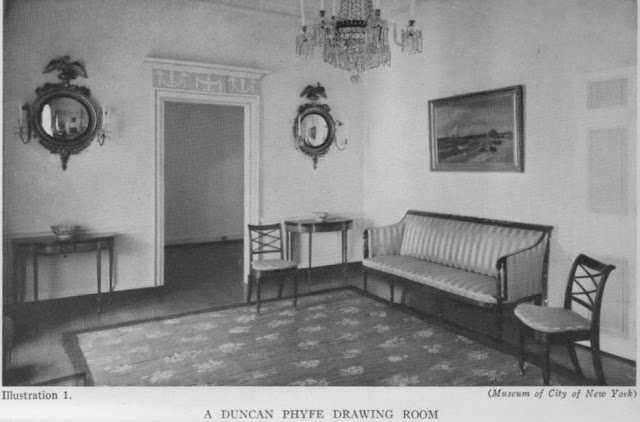

On the morning of July 4, 1776, in the Council Chamber of what is now Independence Hall, a document lay on a handsome flat-top desk awaiting the signature of John Hancock and the other delegates to the Continental Congress which announced to the world in general that thirteen American colonies had forsaken the political bed and board of his Britannic Majesty for, to them, good and sufficient reasons therein enumerated. The desk is still preserved in that historic building in Philadelphia, and aside from its political significance is a fine example of the restrained skill of an unknown craftsman in that city (Illustration 1).

When the Federal government was for a brief period located in New York, that city's venerable Statehouse given a new front, refurbished, and renamed Federal Hall. Among the pieces of new furniture - $50,000 was provided for these changes - was a presidential desk. It is now to be seen in the Governor's Room in the City Hall. There is a touch of Sheraton to the design, but fundamentally it is closely akin to the one in Philadelphia; and both are amply designed for their use, a desk at which an official might sit and transact his public business. No pigeonholes in which important papers might be mislaid. Just and expanse of top supported by two tiers of drawers on either side. Then as now, it was an efficient piece of furniture for a man of affairs.